Celebration

of Stories

Five sculptural

artworks created in dialogue with stakeholders in agriculture and food

related interests.

Corn Crib, Silo and Elements

Artist: Karl Lorenz

wood,

paint, photographs, concrete silo staves

(8'H x 12'L x 9'W)

This sculpture, Corn-Crib, Silo and Elements, reflects many streams of interest drawn from interviews with a diverse range of communities involved in the food system. The central wooden construction in the sculpture is abstracted from vernacular farm architecture and open storage structures to create the central focus -- part corncrib; part home; part altar.

The move from hunter/gatherer to sedentary communal living relies on the ability of a people to store a surplus of food, and one main theme of the sculpture is storage. The wooden structure is derived from wooden corncribs, once a common occurrence in the upper Midwest. The upright blocks are concrete silo staves, used to build concrete storage silos. While people have learned to harvest and store a surplus of food, many communities were careful to remind us that agriculture is, ultimately, based on the primary relations of Earth, Air, Fire (sun), and Water. This theme is suggested by images affixed to the structure. Some communities have also insisted that, as a society, we need to learn to be better neighbors, relatives, to the interlocking communities of beings that support and are supported by the land.

Our ability to generate large-scale impacts on the land through farming demands that we accept the responsibility for understanding these effects. As humans, we also have the obligation to be good neighbors and appreciate how we are nurtured by the many cycles that support a healthy ecology. We need to humbly hear and respect the many stories on the land, while reciting our own.

Migrant Worker--Alonzo Morales

Artist: Gary Desosse, ceramic by Kaveh Shakikhan

hydrostone,

ceramic, wood, copper

(4.5'H x 7'Diameter)

This sculpture integrates three main elements. The first element as symbolized in the poster is the bowl -- the container, the holder of the food, the most primary food implement -- before even the digging stick, the first artifact of agriculture was the bowl. The second element is the machine -- the industrialization of agriculture. The third, and most important element, is the migrant worker, the figure of a person, symbolizing an oft-overlooked community. As the sculpture synthesizes these three elements together, both structurally and metaphorically portraying the story of the migrant worker.

The figure of the migrant worker is hunched, the slope of his back creating the shape of the bowl. In its most literal sense, our nation's food supply rests on the backs of their labor. The figure is cast seven times mimicking the repetitiveness and depersonalization of the industrialization process. This circular repetition of figures, holding implements, also creates the impression of a turbine further underscoring dehumanization of the work. Structurally trapped between the nation's cornucopia and the industrialization of farming is the migrant worker. He is locked in this system and is an inextricable part of the structure that supports our nation's food supply.

There are other subtleties in the sculpture, like the small Bible in his top, left pocket referenced in the poster interviews. The bowl itself is lined with clay tiles like broken pottery fragments.

The figure is based on lifelong migrant worker, seventy year-old Alonzo Morales. In telling his story, he offered merely one complaint -- in all his years in the fields, no farmer ever brought him a drink to quench his thirst. He carries an expression on his face -- one that does not suggest pity or protest, but a simple request to acknowledge his humanity.

Urban/Rural Interface - At the Table

Artists: Karl Lorenz, Kaveh Shakikhan

wood, paint,

screened images on ceramic tile, ceramic, copper, photo-transparency

(42"H x 9.5'L x 5'W)

This sculpture evokes the interaction of the largest "feedlot" the metropolitan area -- and its sustainer, rural America. The images employed to represent this contrast are aerial photographs of Minneapolis and a rural food production region in Minnesota. The scale of each image is identical, but the contrast in relative population density is obvious. Consumption, the final chapter of the food system, is portrayed at the nexus of the rural/urban interface.

Traditions that bring family, communities and cultures together manifest in the foodways of societies. We all gather to share the fruit of the land around the table. The tables depicted in this work represent both dinner table and worktable. The romance around the table and thoughtless consumption of food is challenged by need to understand the complex reality of need and production in the food system. The dining table tells the story of foodways, families and fellowship. The aspect of worktable suggests the learning required to understand the breadth and connectivity of our food system.

This piece treats the complexity of the rural/urban interaction as well as the intimacy and fellowship of the table. Ultimately, what we grow, we will consume, and we live the consequences of how we grow our food. Custom and interdependency define both of these aspects.

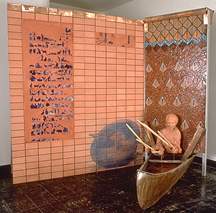

Ricer

Artist: Kaveh Shakikhan, canoe and ricer by Gary Decosse

wood,

terra cotta, copper, screened images

(7'H x 8'L x 6'W)

This diptych depicts the the interplay of food and the land in Minnesota, as told by different cultures. Glazed glyphs, representing commonly recognized icons of the family farm, celebrate the legacy of European immigrant settlement and agriculture. Mounted on cracked, unglazed terracotta, these images are impressed upon clay that suggests the earthiness and texture of soil. At the nexus of the two panels is the image of a cast iron kettle filled with parching wild rice. This 'trader kettle' and its contents portray the long cultural interaction and merging of traditions of European settlers and traders and indigenous people of the region.

The agricultural glyphs are contrasted on the other panel by a figure, glazed tile, waterwall, and copper canoe. This panel depicts the story of the Anishinaabe people, brought here by prophecy to harvest the 'good grain that grows over the water' -- wild rice. The tile wall suggests the opening of the germplasm of the rice -- depicting possibility, renewal and nourishment. The water flowing over the wall reminds the viewer of its role as the ultimate giver of life. The figure suggests a traditional and gentle harvest knowledge, using wooden beaters to bring wild rice into the canoe. Close to the water, connected to their wild food source, and linked to a long tradition, the Anishinaabeg continue their ricing tradition today. American Indians and European-descent farmers continue this dynamic relationship of interaction around food, land, tradition and harvest.

Rebirth of the Prairie

Artists: Gary Decosse and Karl Lorenz

wood,

paint, porcelain, terra cotta, photographs, soil core samples

(10"H x 8'L x 5'W)

In talks with Native American community members in South Dakota, we were told the story of the White Buffalo Calf Woman. Following the prophecy of the white buffalo calf, this piece engages the complex legacy and fragile future of the American prairie -- the most compromised ecosystem in North America. The bison was the most visible species to vanish from the prairie. The small family farm and ranch are not far behind. These very entities that disrupted its ecosystem in the first place now face the same fate. Lakota prophecy dictates that when a white buffalo calf is born, an era of restoration and healing will emerge on the landscape. Native people, endangered animal and plant nations, and traditions will be reborn. The entire community of the prairie will begin to heal.

This piece evokes the power of the prairie, its difficult legacy, and the possibility of reconciliation and renewal. The images are aerial photographs of the Cheyenne River Reservation, located in the heart of the North American prairie. The reservation is also home to a grassroots, community effort to restore the bison to the prairie and the Lakota people to health. Soil core samples in the work allude to the analytical approach to the land taken by science. Bison emerging over the sculpted prairie speak to the heart and promise of myth and realization of prophecy. The medicine wheel (four colored porcelain markers) centers on the promise resulting from the birth of the white buffalo calf.

The interplay of science and native tradition in this piece suggest the story of European and indigenous interaction on this vast tract of North America.